3 Perspectives on the Opioid Crisis in WC

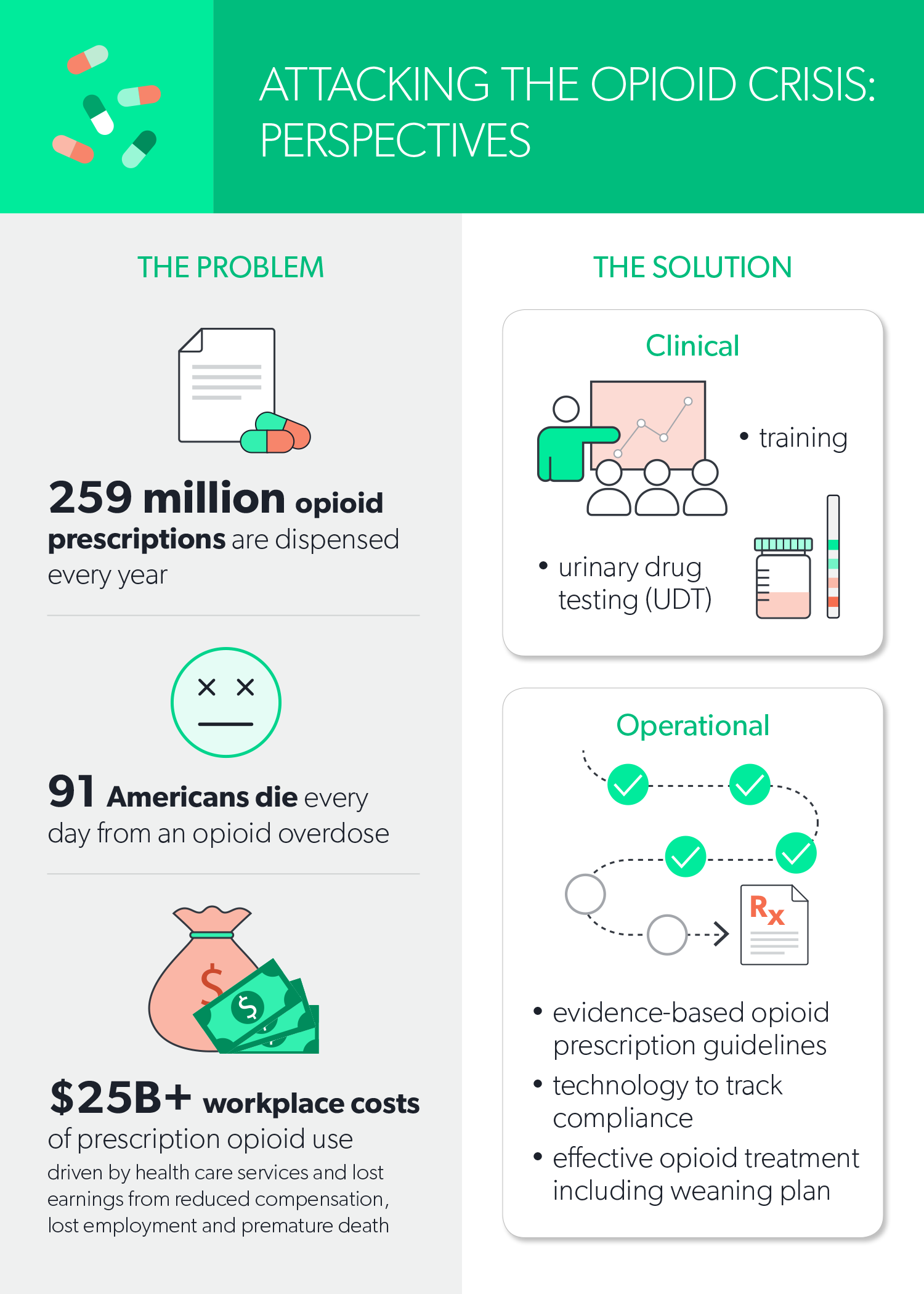

Over the past two decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the use of opioids in workers’ compensation. Opioids are being prescribed for many conditions for which they were not originally intended. Efforts have begun across the U.S. to create opioid treatment guidelines, change medical practice patterns and curb the opioid epidemic. While much has been written recently about the unintended consequences of opioid use, such as how they increase pain sensitivity and level of disability and can lead to addiction, there is little information available about the perspectives of the key players in workers’ compensation on the opioid issue.

Mark Pew, a prominent managed care organization’s spokesman, has said, “Using opioids as a crutch really is the wrong thing. What you need to be focusing on is coping with it and managing it like the vast majority of humanity does with chronic pain or just the fact of getting old.” But what do the injured workers, physicians and claims adjusters say? I conducted confidential interviews with members of each of these groups to get the perspectives of those who so far have had less of a voice in the debate.

Physicians

Physicians must balance their desire to control their patients’ pain against the known drawbacks of opioids. One physician told me, “When I was in medical school 20 years ago, we were told that we were undertreating pain. Pain was named ‘the fifth vital sign’ (along with blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature), and we were trained to ask patients about their level of pain on a 10-point scale at every visit. At that time, very little was known about the dangers of long-term opioid use. Now, patients with any kind of pain have come to expect to get that narcotics prescription when they see the doctor.”

Interestingly, in response to the current opioid crisis, delegates at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Medical Association passed a resolution recommending that pain be removed as the fifth vital sign in professional medical standards. Critics, many of them pain management specialists, say the move “will make it even more difficult for pain sufferers to have their pain properly diagnosed and treated.” However, a 2006 study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine concluded that “routinely measuring pain by the fifth vital sign did not increase the quality of pain management.”

Another physician, a medical director at an insurance carrier, said, “When I see the second opioid prescription come through the system, I start reserving for detox.” She meant the second opioid prescription is an indication to her that there is a high likelihood the injured worker is going to become addicted to the opioids.

Claims Adjusters

Claims adjusters have a unique perspective on the direction a workers’ comp claim takes. They usually speak with both the injured worker and the provider and can influence the process to a certain extent. One claims adjuster said, “I’ve been watching the whole opioid crisis unfold for the last 10 years. We see the opioid prescriptions coming through, and we know that many of them are not indicated by the patient’s condition, but we have limited options for preventing problems. It would be nice if we could identify the providers with good prescribing patterns and direct injured workers to those providers.”

Another claims adjuster told me, “In states with drug formularies, where opioids require prior approval, we are seeing much less opioid use on new claims. Our biggest problems are the older claims where the injured workers have been taking opioids for long periods of time. Then we start to see the prescribing of additional drugs just to treat the side effects of the opioids. The worker is already addicted, is not even getting adequate pain relief anymore, and the claim just goes on and on.”

This claims adjuster thought the best approach to the opioid problem would be to have a claims management system that alerted managers every time a new claim had an opioid prescribed. That way, “we could immediately contact the physician and make sure there was an understanding of the opioid treatment guidelines and a plan in place, right from the start, for weaning the injured worker off the drugs at the appropriate time.”

Injured Workers

In the current climate of awareness about the risks and dangers of opioids, injured workers are often caught in the middle. They must balance their desire for pain control against their growing concerns about side effects and long-term adverse effects. One injured worker said, “I know I’m getting less pain relief than I used to from the pills, but I’m reluctant to tell my physician because I’m afraid of having to deal with my pain on my own. I’d rather suffer with the side effects I’m accustomed to than risk being in constant pain again.”

Another injured worker told me, “I went from eight pills a day to being totally opioid-free, but it took two stints in rehab and a whole lot of willpower. It’s a seductive thought, to place your trust regarding pain relief in a pill, but it’s not a long-term solution. The pills have too many disadvantages. Sooner or later you have to get off the pills and take control of your pain using other methods.” This injured worker has achieved an acceptable level of pain relief using over-the-counter medication and by practicing mindfulness.

A third injured worker reported, “I’ve been on opioids for two years now. My doctor keeps refilling the prescription, so I keep taking the pills. I have a lot of side effects, but it’s worth it to keep my pain under control. I don’t want to make any changes in my regimen and risk being in pain again. I find the negative publicity about opioids very scary. I guess someday I’ll quit them, but just not right now.”

In conclusion, injured workers, providers and claims adjusters are all seeking the right way to deal with pain. Injured workers in pain need pain relief, but they also need non-pharmacologic pain management techniques. Most treatment guidelines in workers’ compensation now recommend opioids only for acute, post-surgical pain relief for three to seven days, ideally. They are not recommended for chronic, musculoskeletal pain, e.g., for pain lasting longer than three months. Providers must take responsibility for engaging their injured workers in an active pain-management process. It doesn’t have to be a formal program; it can be an agreement between doctor and patient. Doctors have to be ready for this responsibility if they prescribe opioids; it’s poor practice — and violates the physician’s imperative to “do no harm” — to prescribe something addictive if you are not able to assist the injured worker with the weaning process.

For their part, injured workers must accept the necessity of being actively involved in their pain management and buy into not taking pills long-term that are going to result in more harm than good. They should demand that their prescribing physician discuss the medication plan with them, what the adverse effects are and what the weaning process will be like.

Finally, claims adjusters have the responsibility to be on the lookout for opioid prescriptions and to make sure that providers are prescribing them within guidelines. There are technological solutions for this. The best approach to the opioid crisis is a team approach: providers, claims adjusters and injured workers working together to avoid opioid dependence and maximize recovery, restoration of function and lasting relief from pain.